In this series of interviews freelance writer, Louise Turner has been speaking with leading voices in climate activism. She speaks to Keke about food origin stories, how we connect to the food we eat and more.

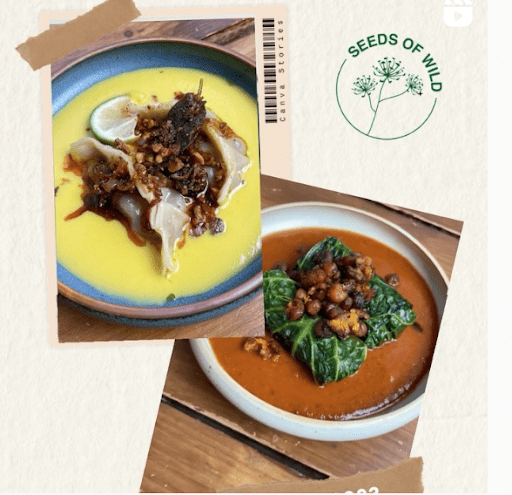

Kerran Kaur, ‘Keke’, is a self-taught baker and chef based in London. She is passionate about the reconnection of food and people, tracing the origin stories of the diverse cultural histories of our produce, and bringing her Indian heritage to her work. Keke foregrounds locally grown food, ensuring accessibility of a healthy diet for all and knowledge as power (and inspiration) when it comes to what we eat. She’s a head chef at The Fields Beneath and guides businesses and restaurants in plant-based development in her consultancy Seeds of Wild. Keke works with communities and holds workshops and regular supper clubs to share her knowledge, recipes and commitment to a plant-based, ethical, just food system. She will create a locally and community-sourced menu for Wen’s food justice event this February.

Keke, thank you so much for speaking with me. You’re a self-taught chef and baker; what started you on this journey?

My family. I come from a huge family that always cooked from scratch. Most of my family is Punjabi, so North Indian, and there’s a rich tradition of cooking. I’ve always done it. It was the thing you do.

“Something simple like being able to provide food for yourself is almost like a revolutionary act because it sparks something.”

Why are food origin stories important?

We need to start appreciating all of our resources! There is such a disconnection at the moment as to how we get things, where they come from, how they’re grown or how long it takes [to grow them]. It’s easy to forget how far removed we are from daily production. So it’s important to tell these stories. It highlights the work people do to produce the most simple things so we can have this convenient life. It’s not only about where we’ve come from too. It’s important to know where the future’s going and for us to ask questions.

How have people responded to your work around this?

Really really well. A lot of stories because I’m embedded in this food system; I forget when I first learnt them. Then when you’re telling somebody [something] for the first time, they say, are you serious? That moment I’m like, wow. This isn’t a given. A lot of these stories aren’t obvious.

Then I’m like, this is great. This is what we want. We want people educated and informed so that they can make good decisions. People are like; I can’t believe I didn’t know! I consume this all the time. I didn’t know where it came from, that it took so long to grow, that you had to grow it like this, that it’s so water-intensive.

We take for granted that people will know [about their food], and it’s not because they don’t want to but because there’s just so much information. So, yeah, it’s been met with a really nice response. It’s given me room to go further because people really want to know this information.

That’s fantastic. It’s really positive to hear.

Do you see a disparity in socio-economics around people being able to access more locally grown food?

Do you see a disparity in socio-economics around people being able to access more locally grown food?

Yeah, massively. Depending on where you go, there’s such a huge shift in availability, and obviously, part of it is because organic, artisanal, or locally grown things take more time. So they’re more costly because of man hours and things like this. But it’s also about an assumption about what people eat. They might have never been exposed to something before, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a market for that. Many people would love this and want access to it, but there’s nowhere to get it where they live within their budget. And it can be budget-friendly.

The biggest thing that people tell me is that buying from a farmer’s market is expensive. I want to buy things that are good for me, but I also have a budget! I’m not a millionaire. I think it’s important to change the perception of these things that are better or healthier for us because we just assume organic food is super expensive. We can’t afford it, so we’re not going to try. How can we include these things in people’s diets in a way that they can afford? Having access to growing is one of the simplest ways to do that.

It loops back to the time-cost issue you mentioned, as it takes time to grow food…

Exactly. It’s like, I’d love to have an allotment in an ideal world, but I’ve got work every day because my rent’s expensive, and I’ve got kids and all of these things. So supermarkets and shops provide convenience for us. They take the growing part out of it, but somebody still has to grow that [food], and how are they doing? It’s this double-edged sword. If you buy it cheaper and from a supermarket, somebody is being exploited. It might not necessarily be you work-wise, but you are being exploited by being sold food that’s terrible for you that uses pesticides. Then you are inadvertently contributing to problems like climate problems because you are purchasing this food. And it’s not something you wanted, but you have no other choice. Then the people growing our food don’t have a choice either.

It’s trying to make it work for everybody in the chain. It’s finding solutions for people who are already growing things, finding supply chains for them and markets for them to sell so that they don’t need to sell at this huge premium because they know they’re not going to sell everything a lot of the time. Then a lot of it goes to waste.

So, how do we find producers that want to produce in a way that’s great for the environment and themselves so they can afford to produce and find a big enough pool of people that can afford to pay a reasonable amount for that product. It’s possible. Even going to the farmer’s markets, I mean, the one I go to, I have to be a bit organised because it’s only once a week, so you have to go prepared. But, how can our preparation help us with saving money and having access?

How might a deeper connection with what we eat foster a more just food system?

It’s about appreciation. A deeper connection to your food gives you a different mindset. You don’t want to waste it. You don’t see it as something disposable. It gives you a much deeper appreciation of the land and what it can do for us. You marvel at it. Wow. If you plant this seed in the ground and keep watering it, you’ll have something growing that can nourish you and provide energy. Access to that; it’s this sense of autonomy.

Being able to produce food for yourself and having access is so important in the current climate where we’re constantly told that we don’t have options and choices. Something simple like being able to provide food for yourself is almost like a revolutionary act because it sparks something. It’s like, oh my god, everything I need I can somehow provide within the realms of a community working together. We can do this together. It’s empowering, and it gives you a bit of a revolutionary attitude for life. I think it gives you so much resilience because you see all phases. You see things grow and flourish and then die. Then happen again in a cycle. It makes you very resilient.

What has this work brought you in terms of your own connection to food?

It’s definitely strengthened more since I’ve become plant-based. And everything that happened with Covid for me. I come from Punjab, which is [a region in] Northern India. It’s very arable, mostly farming, the bread basket of India. I’m not super religious, but I’ve always known my heritage is people who have provided for many people—a heritage of farmers.

I’d sort of forgotten about it but then, deciding to go plant-based, it started to make sense. Starting to work with vegans and understanding activism of food and land. I was always politically active but trying to seek that kind of food justice made me look at how things were produced more. I used to consume a fair amount and loved flavour and for things to taste great. As a cook and chef, you love good quality. So generally, you’re looking at where it comes from, how it’s made, that kind of thing. But then there are so many other things that I just didn’t think about. When it comes to organic things, you know why it’s good for you. It’s organic, so it doesn’t use pesticides. But then, I wasn’t thinking about pesticides. I was looking at the end product and going, ah, that’s beautiful and lasts a long time. It’s very practical for me. I was also fitting food into convenience.

I was eating food from my heritage. So, obviously, that’s important stuff. But then, as I went along this journey, and became more plant-based, I started looking at organic systems, biodiversity and permaculture and understanding what these things were and how they benefit the people that grow directly. I’m always looking for justice in some way. When we talk about things like racism, I’m talking about that in a removed setting in England. I’m not looking to my own people that are producing stuff which is coming over and how that has grown!

I was eating food from my heritage. So, obviously, that’s important stuff. But then, as I went along this journey, and became more plant-based, I started looking at organic systems, biodiversity and permaculture and understanding what these things were and how they benefit the people that grow directly. I’m always looking for justice in some way. When we talk about things like racism, I’m talking about that in a removed setting in England. I’m not looking to my own people that are producing stuff which is coming over and how that has grown!

Where did this take you to?

I looked at a lot of it in regard to spices. Spices are one of the number one things diaspora people from India export because that is the first thing that’s going to make things taste like your culture, heritage, and traditions. But looking into it and seeing how heavily pesticided they are, how polluting and how little profits go to farmers and workers. I’m just like, this is the core of our identity, and we’re exploiting the peoples that haven’t left.

We still have a huge connection to them. We’ve got family back there and looking at that, especially at the farmer’s protests, how the government was treating them. Then at the green revolution and understanding where this all stemmed from.

It’s got to a pinnacle of distress now, where people cannot take it well and leave their livelihood for a year to protest! We need to listen to this. We need to look at this to make these people an example. For people like me, this is my heritage, where I come from. These are my ancestors. People I share things with. Now, these are people I buy imported goods that they’ve grown, and they’re screaming at us, telling us this is unfair. We can’t live like this.

So for us to live the way we live here, they have to live like that. That can’t be right. There must be a better way. In the same space, we waste half of the food that we have! This is broken. This cannot make sense. So that’s the kind of thing that really pushed me. I felt justice is something we have to strive for. It’s a basic necessity.

“My heritage… my ancestors… Now, these are people I buy imported goods that they’ve grown, and they’re screaming at us, telling us this is unfair. We can’t live like this”

Thank you, that’s really powerful. In reaching this point, what would food justice look like to you?

So many exciting things! Definitely more small-scale urban farming, people giving up small pots of time in exchange for different types of food. The co-ops we have where we can buy from much smaller organisations, a lot of shared learning, sharing skills because these skills are being gatekept by big corporations.

I think it’ll be a rearrangement of priorities as well, with companies able to offer all-around services that include lots of payment options. So people with a job that allows them to be more time-rich, the way they buy would look slightly different to somebody whose job is quite physical and intensive. Maybe they’d walk home with something different [bought] in a different way like some type of bartering.

I think it’ll need a lot of education and participation. We need to participate more in all of this – our food system. That’s maybe one of the biggest problems. It’s not necessarily because we won’t or can’t. We aren’t facilitated. Nobody wants to facilitate us because supermarkets are super convenient and provide everything for us, but I think people want this kind of shift to happen. They know that it’s not right [the current food system], but they just don’t have the answers to what would be the best. It will look different for each community, depending on where they are. But it does involve community-based cooperation, definitely, that puts people at the centre.

Thank you so much for speaking with me again, Keke.

Do you see a disparity in socio-economics around people being able to access more locally grown food?

Do you see a disparity in socio-economics around people being able to access more locally grown food?